FORORD

DENNE UTGIVELSEN inngår i Grønn Industri 21, som er en utredning og en «dugnad for utslippskutt globalt og industriutvikling nasjonalt». Akkurat dette notatet er foreløpig på engelsk, av hensyn Grønn Industri 21s akademiske samarbeidspartner, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose ved University College London.

For klodens klima, som for norsk økonomi, ligger mye av løsningen i grønn industri. Med denne erkjennelsen vil Grønn Industri 21 forene grupper som ellers polariseres.

Norge har lange tradisjoner innenfor industri. Vi har teknologi som kan bidra til det grønne skiftet innenfor energiproduksjon, maritim transport, karbonfangst, kraftforedling og marin industri.

Utredningen Grønn Industri 21 vil utforske disse mulighetene: Kan Norge bidra til utslippskutt globalt på en måte som utvikler grønne arbeidsplasser nasjonalt? Kan vi forene statens finansielle styrke og næringslivets tekniske kompetanse i en handlekraftig klima- og industripolitikk, som også kan forene miljøbevegelsen og fagbevegelsen?

Vi vil nok fortsatt være uenige om viktige veivalg for oljenasjonen Norge, men at vi må jobbe sammen for å finne nye og bærekraftige løsninger, er vi helt enige om.

DUGNADSKOMITEEN FOR GRØNN INDUSTRI:

Framtiden i våre hender

Atle Tranøy, Fellesforbundet og Aker ASA

Jørgen Randers, klimaveteran

Manifest Tankesmie

NTL

GRØNN INDUSTRI 21 ER FINANSIERT AV

Kværner

Aker Solutions

LO i Aker ASA

Industri Energi

NTL

INTRODUCTION

THE NORWEGIAN ECONOMY is dependent on the petroleum sector. This means that a large part of the economy is dependent on a finite resource and the production of future CO2 emissions. In 2018, around 21 percent of tax revenue came from the extraction of oil and gas. Gå til fotnote nummer 1 In 2019 crude oil, fossil gas and condensate constituted around 47 percent of total Norwegian exports. Gå til fotnote nummer 2 But as stated in the government’s White Paper on Industry Gå til fotnote nummer 3 and by the government's Productivity Commission Gå til fotnote nummer 4 the role of petroleum extraction in the Norwegian economy will dwindle.

In 2012 the International Energy Agency IEA reported Gå til fotnote nummer 5 that only one third of existing fossil fuel reserves can be consumed if average global temperature increase shall be limited to 2 degrees. The figure illustrates the urgency of a green transition and therefore the potential risks for future employment, incomes and profitability in oil-dependent countries like Norway. The clock is ticking for both Norwegian capital and labour to end the petroleum dependence and diversify into new sectors.

The purpose of this paper is to shed light on the decline of mainland industry and clarify the need for a new and active green industrial policy for Norway.

Is industry still important? A dichotomy often used to differentiate between countries that are rich and poor, is that of “industrial” versus “developing” countries. The debate in the field of economics over development and industrialisation has produced a vast body of literature over how to divide between rich and poor countries, how and why they became rich or poor, and the use of GDP for measuring inequalities between countries. But industrialization is widely considered to have been essential for all the countries we now classify as “rich” since industrialization is one of the simplest ways to increase output per manyear.

It is in this light we should look at the state and historical trends of industry in Norway. Manufacturing has given way to a growing dependency on the export of commodities such as fish and petroleum. Apart from sustainability issues, there are also serious economic disadvantages with an economy specialised in the extraction of raw materials. Volatile international commodity prices have a large effect on domestic profit, incomes and employment (last experienced in 2014-2016 when oil prices plummeted) and other countries will capture most of the value added as Norway exports basic goods for others to process. Industry directs innovation, as the high-tech industries of the future are built upon the technologies, skills and research of the high-tech industries of the present. A shrinking role for industry is not a good development for Norway.

There is an emerging consensus in the political sphere of the need for domestic industrial development. Gå til fotnote nummer 6 As the productivity commission of 2015 wrote: Gå til fotnote nummer 7

“The oil sector will no longer be an engine for growth, and new industries have to take over. Industries connected to the oil sector have grown into internationally competitive exports but at the same time costs have risen and suppressed old industry. In the future activity in the oil sector will fall and have a diminishing role in the Norwegian economy.”

Industrial and climate policy needs to be informed by both the needs of the Norwegian economy, and the needs of the global climate.

INDUSTRIAL POTENTIAL

NORWAY HAS SEVERAL WORLD leading industries. The expansion of hydro power in the early 20th century gave Norway low energy prices and thus a competitive advantage. Now the power intensive manufacturing industry is exporting at a value of around 100 billion NOK per year, with low CO2 emissions. Since the 1990s, the power intensive manufacturing industry has reduced its emissions by 40 percent at the same time as revenue has increased by 37 percent. Gå til fotnote nummer 8

The shipbuilding industry is another key section of the Norwegian economy. Recently, there has been a growing demand for electric and hydrogen ferries Gå til fotnote nummer 9 and it is likely to grow as both domestic and foreign maritime sectors aim to reduce their operating costs and carbon emissions. Gå til fotnote nummer 10 The revenue impact company Markets and Markets Gå til fotnote nummer 11 estimate that the market for electric ships will triple between 2019 and 2030. Shipbuilding has the potential to be a central element in the Norwegian green transition.

Problems originating in fossil fuel extraction should not be conflated with the innovation, skills and technologies that have arisen out of the petroleum industry. These competences can be used for entirely different energy sources, like geothermal energy. Gå til fotnote nummer 12 Geothermal energy is based on the heat arising from the Earth’s core, and can be an important future source of low-carbon energy. Transitioning into such low-carbon industries, to which there are porous barriers to entry will be important for the Norwegian petroleum industry.

The petroleum industry has also given rise to a large petroleum-related manufacturing industry. This is an innovative sector of the economy that produces the platforms, subsea equipment and drilling tools, and other machinery needed for the extraction of petroleum. At 370 billion NOK in 2017 it is the second largest industry in Norway by turnover, and constitutes 1100 businesses that employ around 86.000 employees. Gå til fotnote nummer 13 This sector also needs to be mobilised in the transition away from fossil fuels, and there are several opportunities in for example carbon capture, floating offshore wind, geothermal and other low carbon industries.

These are some of the high-skill, high-tech industries that have bloomed within the Norwegian variety of capitalism, and ensured employment and income for generations of Norwegians. In the book Varieties of Capitalism Gå til fotnote nummer 14, Hall and Soskice define Norway as a Coordinated Market Economy (CME) along with countries like Germany, Japan, Sweden and Denmark. Firms in these countries rely more on non-market forms of coordination for industrial and inter-firm relations, and relations with the financial sector, than Liberal Market Economies (LMEs).

The Norwegian model was born out of strong labour unions, along with a political will for national sovereignty. It was the aim to keep Norwegian resources under Norwegian control that created the concession laws in the early 20th century, restricting private ownership of domestic hydro power to limited time periods. Gå til fotnote nummer 15 The development of state ownership models in the 1940s and the active state involvement in the oil and gas industry in the 1970s are other key historical points that shaped the Norwegian form of capitalism. It is a capitalism with a strong democratic influence.

More than a century's worth of fruitful experience with the Norwegian variety of capitalism should inform the industrial strategy for Norway’s transition away from fossil fuel dependence. Democratic influence in the economy and non-market forms of coordination has been a successful recipe for Norway in the past and could be so in the future.

INDUSTRIAL DECLINE

WHAT IS THE CURRENT STATE and trend of Norwegian industry? According to recent Minister for Trade and Industry Torbjørn Røe Isaksen “Industry goes well.” Gå til fotnote nummer 16 The Conservative politician claims that “the green transition is happening while Norwegian business and industry is flourishing.” Gå til fotnote nummer 17 Realities are less rosy. Despite having several world-leading companies with the potential to make serious contributions to the global green transition, Norwegian industry is in decline.

The green transition will require the manufacture of technology, machinery and products that can supply the world with clean energy, enable electrification and lower energy use. Manufacturing wind turbines, solar panels, machinery for carbon capture and a host of other goods could thus be a route to both lowering world emissions and developing a new domestic “engine of growth.”

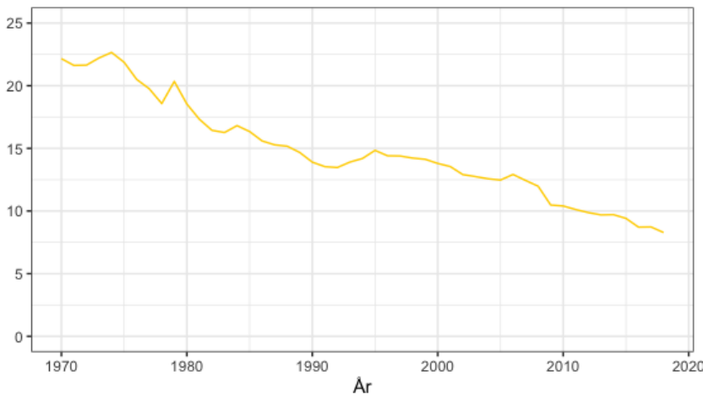

In 1970, manufacturing constituted more than 22 percent of Mainland Norway’s GDP. It has since fallen at a steady pace to around 8 percent in 2018. Gå til fotnote nummer 18

Figure 1. Manufacturing share of Mainland GDP 1970–2018

A declining share of manufacturing in GDP, often called deindustrialisation is not unique to Norway, it has been the case across several western countries. But the Norwegian case has been dramatic. A paper in Cambridge Journal of Economics Gå til fotnote nummer 19 found that apart from Hong Kong and Macao, Norway has had the largest fall of manufacturing as a share of GDP out of the 48 countries studied, including 25 OECD countries.

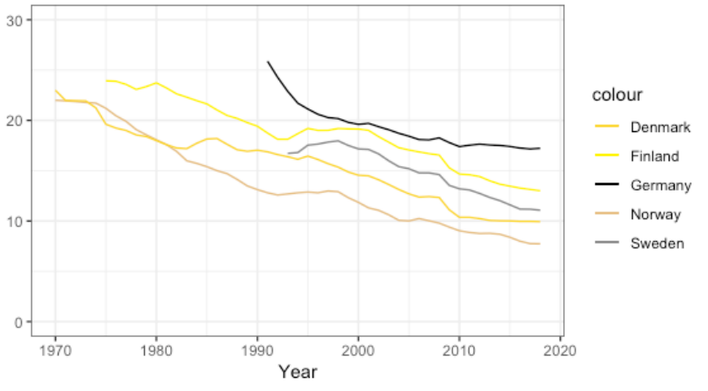

Another method for measuring deindustrialisation is through manufacturing employment. Even using this method, deindustrialisation in Norway has been deeper than in neighbouring countries. Gå til fotnote nummer 20

Figure 2: Employment in manufacturing (% of total)

Manufacturing is far away from being a “leg to stand on” Gå til fotnote nummer 21 that can replace oil and gas for employment.

EXPORT SHARES

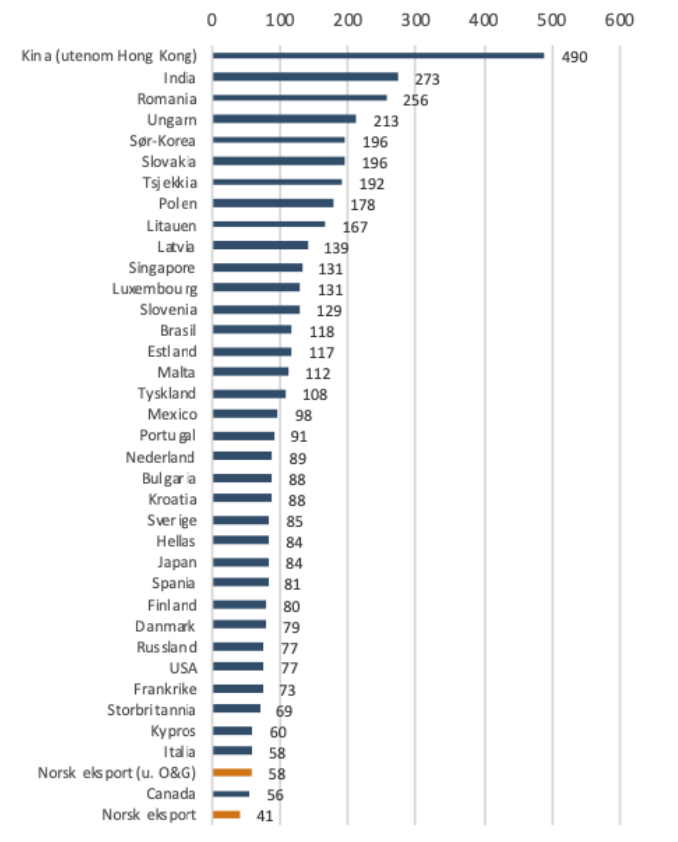

Export markets are a crucial source of demand for the domestic industry in small countries. Norway has historically been a successful exporter, which enabled the growth of large domestic industries that have become major employers. It is therefore worrying that Norway has had the largest fall in the global export share of all OECD countries since 1998 according to a report by Menon economics Gå til fotnote nummer 22 (see bottom of the graph below). As countries like China and India have enormously increased their exports since 1998 it is not surprising that other countries would have a falling global export share. But considering the Norwegian fall is greater than any other OECD country, it is worth questioning whether this is not a consequence of domestic as well as international mechanisms. Gå til fotnote nummer 23

Figure 3: Change in share of global export market. 1998 indexed to 100

Graph taken out of Menon Economics report

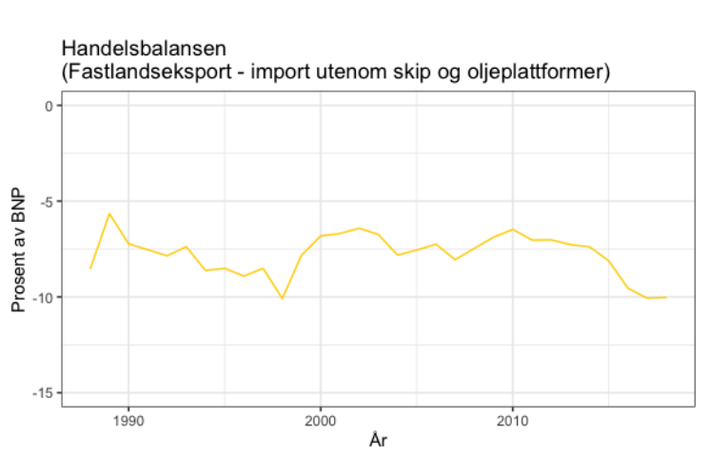

Apart in the change in the export share, we can look at the trade balance. The trade balance is a measure of how much goods and services are exported minus imported. Mainland Norway has for decades had a negative trade balance as seen in the figure below. Gå til fotnote nummer 24

Figure 4: Mainland Norway trade balance 1988-2018

A negative trade balance means that there has been a larger domestic demand for foreign goods than foreign demand for domestic goods. While petroleum has yielded enormous export revenue, it has also made the country highly dependent on a finite resource. Therefore, petroleum is not merely a blessing but also a curse. Norway needs other competitive export industries in the post-petroleum era.

PRODUCTIVITY

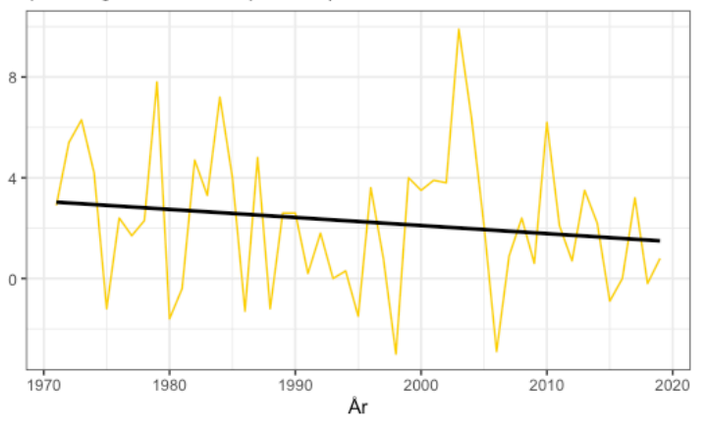

There is a high road and a low road to international competitiveness. The low road is the “cost-cutting” path of low wages, high work intensity and conflictual labour relations and the high road is the “value-added” path of high wages, high productivity and cooperative labour relations. Countries can be internationally competitive either by pushing down wages and having a very high intensity of work, or by having a highly technological and productive economy. Historically Norway has followed the second path. For that strategy to be viable in the future, it is important that productivity growth in export industries remains high. This graph shows the rate of productivity growth Gå til fotnote nummer 25 since the 1970s. Gå til fotnote nummer 26

Figure 5: Change in labour productivity 1970-2018 for Mainland Norway 1970-2018.

Labour productivity growth has a negative trend which undermines Norway’s future competitiveness. While the domestic debate on the viability of the welfare state tends to focus on the share of people in employment, the question of productivity growth is at least equally important. Norway has for the last decades had one of the highest wage growths relative to productivity Gå til fotnote nummer 27 out of developed economies. High productivity growth needs to be central to a strategy for the viability of the Norwegian model.

There has also been a negative trend in the change for labour productivity in manufacturing, albeit not quite as steep as on the level of Mainland total. Gå til fotnote nummer 28 See the graph below.

Figure 6: Change in labour productivity 1970-2018 for manufacturing.

EMPLOYMENT AND PETROLEUM

As mentioned, exports are a key source of demand for small countries like Norway. As the petroleum sector is such a large part of the economy, Norwegian workers and businesses are now dependent on the global demand for fossil energy for their employment, incomes and profitability. In 2014 this dependence was demonstrated, as the price of crude oil fell from above $106 per barrel to below $50 in six months. Accordingly, investments in the sector fell, and the fall in demand spread to a variety of industries. People were laid off across the economy and unemployment rose by a third. Gå til fotnote nummer 29

Figure 7: Unemployment 2008-2018

With “few legs to stand on” economically, variations in the price of oil will continue to push parts of the Norwegian labour force in and out of employment. If oil dependence continues, a “green transition” will also imply unemployment for many Norwegian workers.

SEAFOOD

Another plentiful resource in Norway is fish and here there are similar dynamics to the oil and gas sector. The government has pointed to the growth in the seafood industry as a positive sign of industrial development in Norway Gå til fotnote nummer 30, but the question is how much the increase in world market salmon prices and the boom in Norwegian exports of farmed fish has to do with industrial progress.

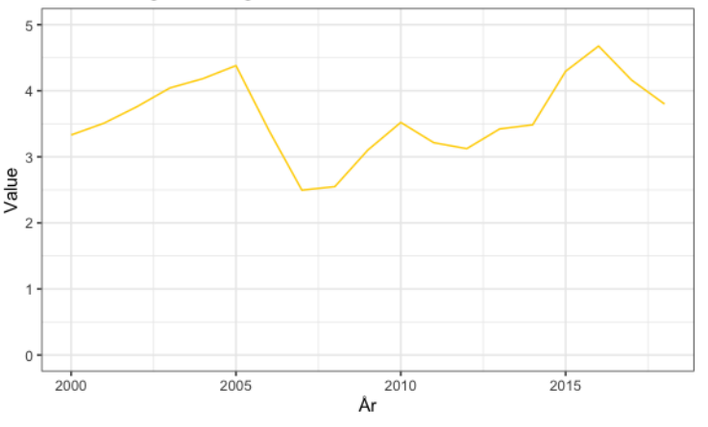

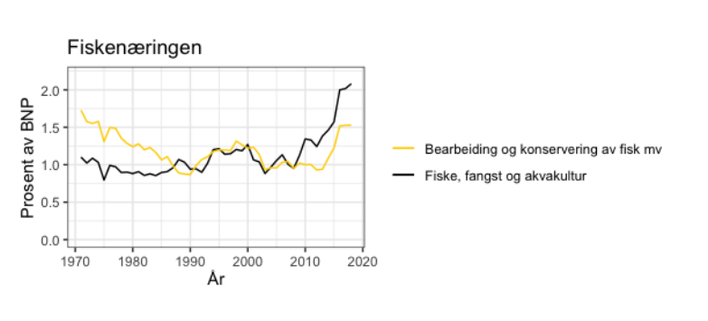

In the graph below is the share of Mainland GDP for both fishing and aquaculture and the processing and conservation of fish products. Gå til fotnote nummer 31

Figure 8: The fishing sectors as a share of Mainland GDP

Both processing and conservation, and fishing and aquaculture has increased as a share of GDP in the last years, but it is the primary resource extraction that has seen most of the growth. For the first time, fishing has overtaken the processing of fish products in value added for several consistent years.

Increased prices and market opportunities has been positive for Norwegian fisheries and aquaculture. Growth in the sector is of course beneficial for Norway in the short term, but seems to reinforce a trend towards becoming more of a primary product exporter with a diminishing role for industrial production. That processing and conservation of fish now constitutes a smaller share of GDP than primary resource production signals that a smaller part of the value chain is retained in Norway.

PATH DEPENDENCE

ECONOMIC ACTIVITY DOES NOT appear out of thin air, but depends on available technologies, capital, skills, and institutions. The green transition is therefore more difficult and costly the larger the gap is between the economy of today and the economy the future requires.

Several opportunities in green industries have already been missed by Norway, such as electric cars, solar panels and wind turbines, opportunities now reaped by other countries like Denmark and China. The missed opportunity in the production of electric vehicles is of extra relevance, since Norway has a large market for electric vehicles. Gå til fotnote nummer 32 This amounts to a collective failure of Norwegian polity, finance and industry.

There are more opportunities to be missed, if current policies prevail. Menon Economics and Eksportkreditt Gå til fotnote nummer 33 have identified floating offshore wind power as a major potential growth market for Norwegian industry and exports. The majority state-owned company Equinor has received support from the public green innovation company Enova for the floating wind project Hywind. But the sum of 2,3 billion NOK merely amounts to around one percent of what the company has lost on its foreign investments. Gå til fotnote nummer 34 This is a good beginning, but no more than a beginning. Floating wind power is rapidly developing in countries like South Korea, USA and Denmark and there is a distinct possibility that Norway will also lose this green market.

Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) is another technology that could produce tens of thousands of jobs in Norway. Gå til fotnote nummer 35 There is additional potential in hydrogen, as well as in electric vessels. Such industrial possibilities must be harnessed, with major investments taking place over the next five to ten years, if Norway is to stop its trend towards industrial decline.

If Norwegian petroleum and mainland industry continues to develop along the current path, the transition towards sustainable industrial development will become increasingly difficult. If investments, technical expertise and employment continue to gravitate around the extraction fossil energy, necessary resources will not go into developing greener industries of the future. In this scenario, the vision spelled out by the Productivity Commission – where other industries are the engine of growth in the Norwegian economy – will become more distant and unattainable.

Without strong industrial development that could in part replace the role of petroleum, Norway could face growing unemployment, a worsening trade balance, slower innovation and more local communities becoming economically unsustainable. Another prospect is increased economic inequality, as industrial unions lose power and influence if the highly unionized, industrial realm of the private sector is dwindling. The green transition requires not only huge investments, but also room in the real economy for the greener branches of industry to grow. They need engineers, skilled workers, managers and suppliers. These resources are in existence, thanks to Norway’s domestic oil and gas industry, but they will not be available for green industrial development, if all of them are employed for the extraction of oil and gas. In that scenario, Norway will sink deeper into dependency on an industry that will, in the world market, gradually diminish.

Policy-wise, the management of this dilemma should amount to pressing hard on the investment throttle and accelerate growth in green industries, while carefully reducing growth in oil and gas. This could enable a shift towards green industries as the engine of growth in Norway. The current government seems to be doing the opposite.

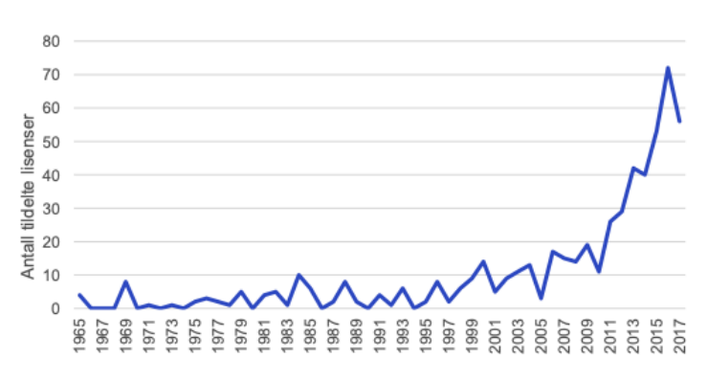

Opening new areas for extraction and awarding new licences is one of the key policy levers for increasing investment in the extraction of oil and gas. Gå til fotnote nummer 36 The number of awarded petroleum extraction licences has grown dramatically in the last years. Gå til fotnote nummer 37

Figure 9: Awarded extraction licences 1965-2019.

This dramatic growth in the number of petroleum extraction licences has, despite all increasing concerns over global climate change, become the chosen national strategy. It is a stark contradiction to the emerging consensus on the need for new industrial development on the mainland.

Each extraction licence represents an initial investment that only becomes profitable over time as carbon is pumped out of the ground and into the atmosphere. The profitability and financial stability of the companies in this sector require that these initial investments yield future returns. The extreme growth in the number of extraction licences promise continued petroleum dependence also in the future, as more of Norway’s resources are directed towards the extraction of fossil fuels. Along this path, resources, capital and labour will not be used to build the green industry of the future.

CONCLUSION

WE OBSERVE A WIDENING gulf between the urgent needs of the economy for new industrial development and the complacent inactivity of political leaders. There is much discussion about the green transition, but actions indicate that political leaders take for granted that oil and gas will be the backbone of industrial Norway in the future, as it has in the past. This entrenchment of path dependence is not just bad climate policy, but reckless industrial policy.

At the moment, the gap between rosy visions and stark reality for Norwegian industry appears to be growing. But it is not too late. Norway has a wealth of natural resources, highly skilled workers and a huge potential within several of the green industries of the 21st century. The green industries of the future can be built upon the foundations laid by the major industries of the previous century. This will require a shift in the strategic ambitions of Norwegian industrial policy.

Noter og referanser

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.norskpetroleum.no/okonomi/statens-inntekter/ (accessed 4/2/2020)

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.ssb.no/energi-og-industri/faktaside/olje-og-energi(accessed 18/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen Stortingsmelding 27, 2016-2017, Industrien – grønnere, smartere og mer nyskapende, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/9edc18a1114d4ed18813f5e515e31b15/no/pdfs/stm201620170027000dddpdfs.pdf, (accessed 2/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen 4 NOU, 2015:01, Produktivitet – grunnlag for vekst og velferd, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/ef2418d9076e4423ab5908689da67700/no/pdfs/nou201520150001000dddpd fs.pdf, page 7, (accessed 4/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen IEA, World Energy Outlook 2012, https://webstore.iea.org/download/direct/141?fileName=WEO2012_free.pdf page 25, (accessed 4/2/2020)

Gå tilbake til referansen In the Government’s White Paper on Industry from 2017, the government spells out a visionthat Norway “should be a world leader in industry and technology”. The Conservative Party write on their website that “Norway needs more legs to stand on” apart from the petroleum industry. As revenue from petroleum falls, and as technology replaces labour, Norway needs “new sources of income”.

Gå tilbake til referansen NOU, 2015:01, Produktivitet – grunnlag for vekst og velferd, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/ef2418d9076e4423ab5908689da67700/no/pdfs/nou201520150001000dddpd fs.pdf, page 7, (accessed 4/2/2020)

Gå tilbake til referansen Industriaksjonen og Manifest tankesmie, For grønt til å være sant?, 2019. page 4.

Gå tilbake til referansen https://frifagbevegelse.no/maritim-logg/norsk-rederi-skal-utvikle-utslippsfrie-ferger-som-nar-lenger-enn-elferger-6.158.607157.c090d06f81, (accessed 5/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.nho.no/siteassets/nox-fondet/rapporter/2018/nox-report---rev8.doc-002.pdf (accessed 5/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/4859241/electric-ships-market-bypower-source-autonomy?utm_source=dynamic&utm_medium=CI&utm_code=h69lkq&utm_campaign=1325660+-+Global+Electric+Ships+Market+Set+to+Reach+%2415.6+Billion+by+2030+-+Increase+in+Seaborne+Trade+Across+the+Globe+and+Growing+Maritime+Tourism+Industry+Drives+Market+Growth&utm_exec=joca220cid, (accessed 5/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://gcenode.no/news/geothermal-energy-can-benefit-from-oil-and-gas/, (accessed 5/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.norskpetroleum.no/utbygging-og-drift/leverandorindustrien/, (accessed 5/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen Peter A Hall and David Soskice, Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, (Oxford University Press: 2001), https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hall/files/vofcintro.pdf page 19, (accessed 5/2/2020)

Gå tilbake til referansen Francis Sejersted, Sosialdemokratiets tidsalder, (Pax forlag: 2005), page 37-38

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/WLpk3G/en-usikker-diagnosefor-norge-torbjoern-roee-isaksen, (accessed 1/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://dagens.klassekampen.no/2019-08-19/debatt-norsk-industri-gront-skiftesant, (accessed 2/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09170: Produksjon og inntekt, etter næring 1970 – 2018”

Gå tilbake til referansen Fiona Tregenna, “Characterising deindustrialisation: An analysis of changes in manufacturing employment and output internationally”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2009, 33, 433-466.

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09170: Produksjon og inntekt, etter næring 1970 – 2018”

Gå tilbake til referansen “More legs to stand on” is a metaphor used by The Conservative Party on their website as they recognise the need to diversify the economy, https://hoyre.no/trygghetfor-fremtiden/hva-skal-vi-leve-av/ , (accessed 2/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.eksportkreditt.no/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Klimaomstilling-inorsk-næringsliv-1.pdf, page 26, accessed (4/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “08804: Utenrikshandel med varer, hovedtall (mill. kr), etter land, år, varestrøm og statistikkvariabel”.

Gå tilbake til referansen We use labour productivity, which is output per hour worked for Mainland Norway.

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09174: Lønn, sysselsetting og produktivitet, etter næring, statistikkvariabel og år”.

Gå tilbake til referansen ILO Global Wage Report 2012/13, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/--- dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_194843.pdf, page 14, (accessed 31/1/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09174: Lønn, sysselsetting og produktivitet, etter næring, statistikkvariabel og år”.

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09174: Lønn, sysselsetting og produktivitet, etter næring, statistikkvariabel og år”.

Gå tilbake til referansen https://dagens.klassekampen.no/2019-08-19/debatt-norsk-industri-gront-skiftesant, (accessed 2/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen SSB data and author's calculations. Time series “09170: Produksjon og inntekt, etter næring, statistikkvariabel og år”.

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidnikel/2019/06/18/electric-cars-why-littlenorway-leads-the-world-in-ev-usage/#627017d413e3, (accessed 5/3/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.eksportkreditt.no/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Klimaomstilling-inorsk-næringsliv-1.pdf, (accessed 30/1/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.tu.no/artikler/norge-risikerer-a-tape-havvindkampen-for-den-erskikkelig-i-gang/483525, (accessed 1/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen https://www.nho.no/contentassets/c7516d8d47b84af9b174c803964b6e75/industrielle-muligheter-og-arbeidsplasser-ved-storskala-co2-handtering-i-norge.pdf, (accessed 4/2/2020).

Gå tilbake til referansen Helge Ryggvik and Berit Kristoffersen, “Heating up and cooling down the petrostate: the Norwegian experience”, in Thomas Princen, Jack P. Manno and Pamela L. Martin (eds.), Ending the fossil fuel era, (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press), 2015, page 249-275.

Gå tilbake til referansen Graph taken from the Cicero report “Redusert oljeutvinning som klimatiltak”, 2017, https://pub.cicero.oslo.no/cicero-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2434201/Policy%20Note%202017%2001%20final%20web.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, (accessed 30/1/2020).